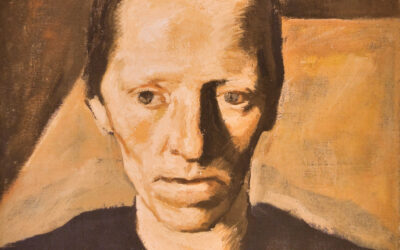

Albin Egger-Lienz (1868–1926)

Carl Kraus (Appeared in: Carl Kraus: Zwischen den Zeiten. Malerei und Graphik in Tirol 1918-1945, Bozen-Lana 1999)

Many labels have been attached to Albin Egger-Lienz: late historical painter, peasant painter, regional artist, blood and earth painter. From a superficial point of view, they are all accurate to a certain degree. What cannot be overlooked, however, is the fact that Egger, above all else, was continually searching for new forms of expression. He himself contributed, in a way, to a stereotypically narrow classification of his work through his “programmatic paintings” that were at the heart of his exhibition strategy and his apodictic statements. His fight with Hodler is legendary, and reinforced its negative effect. The painter disparaged most proponents of international Modernism. In his eyes, their works were playful formal exercises without a deeper spiritual message. “The content fires up the temperament but not some hidden possibilities of an art form. The former intrinsically encompasses all the originality and the appropriate form turns it into art out of “necessity”, of love. On the other hand, art that originates solely in art is only fascination and luxury, “technique”. Only the great background, admiration, quivering exhilaration and love will bring forth true works of visual art. The application of different artistic means or forms seems irrelevant to me as long as it is befitting the subject or born from it” (cited from Kirschl). However: “I couldn’t imagine my last painting ‘Auferstehung’ (Resurrection) without the issue of light (not Impressionism).” In this context Egger points out that he is not painting farmers but shapes.

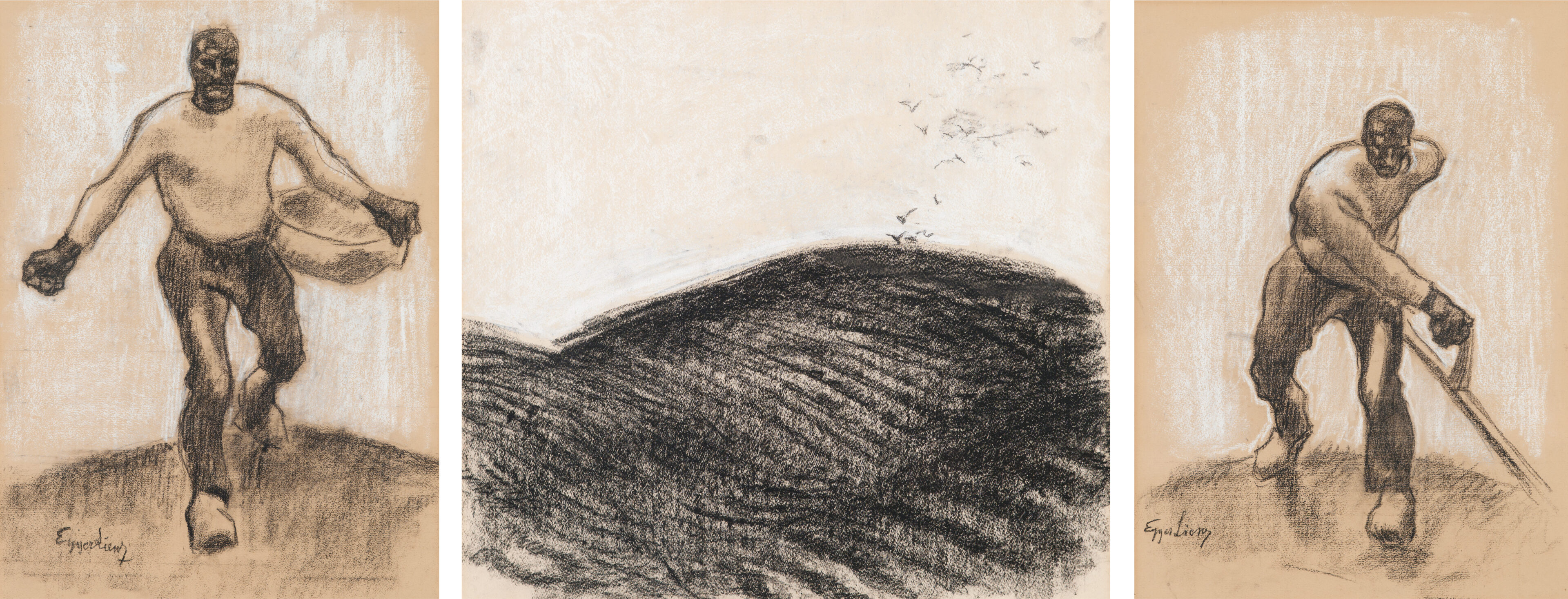

“Der Sämann – Das Ackerland – Der Mäher” (The Sower – The Farmland – The Mower), 3 drawings to the triptych “Erde” (Earth), 1912 (Kirschl Z 331-333; Bozner Kunstauktionen 33, 26.5.2018, no. 359).

It was precisely this relentless struggle surrounding the “problem of pure form on a strict basis of organic nature”, the consolidation of the natural form into the “style from within” that led the painter, especially since the wartime, to ever more impressive achievements. Contrary to Egger’s own statements, parallels to artists of the avant-garde, like Cézanne and Beckmann, can be drawn. This applies to his large compositions but in no lesser measure also to works that he considered secondary: to the magnificently expressive war paintings as well as to the quiet, subdued portraits of his youngest daughter, Ila, for instance. Strictly frontal, symmetrical and executed in the deliberate manner of the old masters, these paintings seem especially solemn and timeless in a classical sense – more timeless than some of his monumental works that he intended to be “eternal” and which are packed with aspirations. These freer paintings include also the two landscapes of Bolzano “Sigmundskron” and “Am Kalvarienberg”. The painter, through intensive transformation typical for his work process, again finds his way from a natural landscape to a greatly balanced, classically quiet composition in rich brown and ochre shades, the hues which dominate his late work. The fact that these landscapes and Ila-portraits are often said to be in the style of the New Objectivity or Italian Neorealism does not indicate his participation in these movements but rather show the artist’s development through his own creative process. However, it is no coincidence that Carlo Carrà, who dedicated several essays to the works of his “Nordic” colleague, admires most Egger’s “classical” œuvre.

After painting the “Kriegsfrauen”(War Women) the painter softened the expressive deformation, which he had taken to severe levels, also in his monumental compositions and arrived at the greatly contemplative style of his “thought images”: from “Generationen” (Generations) and “Mütter”

(Mothers) to “Auferstehung” (Resurrection) and the wonderful finale of “Pietà”. As if he summed up all his life’s work, expression and reality, stillness and motion, spatial-plastic shapes and painterly luminarism now coalesced to form a new entity. All that he desired and searched for, the clichés and effects that can be found now and then in his works during his mid-career, now come together with utmost ease.

Egger’s belief that the expressive means are subordinate to the “big substance” led him to create “images of inherent contemplation”, as he calls them, with unprecedented depth. Within the inevitable destiny of their existence the figures are seemingly far removed, not of this world, mirrors of their peasant being which is sustained by religious sentiments, as well as of the internalization the painter has arrived at: “Religious belief, in the strictest sense of the word, transforms worldly order into a certain otherworldly introspection. This explains the shy nature of mountain dwellers when meeting a man of the world which often is interpreted as distrust, reticence or even narrow-mindedness!”

With his late works, Egger, whose unwillingness to compromise cost him several opportunities at a professorship at the Vienna Academy, moved far away from the public taste. The

“Auferstandene” (The Resurrected) in the war memorial chapel in the city of Lienz caused a fierce controversy which led to an imposed interdict in 1926. His solo exhibition at the Kunstsalon Unterberger in Innsbruck two years prior to that, which was also his first comprehensive showing since the Landesausstellung 1909, was just as controversial. A critic in Innsbruck wrote: “In a current exhibition he shows a ‘Christ’ who is more of a blasphemy than a comforting figure, in ‘War Women’ a woman at the spinning wheel with her hand in the air, where the viewer has to imagine the distaff on his own, in the background naively painted wall benches, mostly distorted, like most other images. They are all template-like in color and concept and offer variety only in the crooked limbs or deformed and distorted coarse bones causing amazement which, however, is rather puzzling, daunting and repulsive…”

When Egger died in November 1926, Tyrol lost its most important artist. None of his painter colleagues had, at that point, accomplished what he had, namely the almost total identification with his work. A leading figure in the Tyrolean art scene was perhaps Artur Nikodem who finds recognition mainly in Germany. However, most frequently compared to Egger is Friedrich Hell who, according to Max Weiler, describes him, like Egger-Lienz, as “a mountain”, not easily accessible but with wonderfully evocative power.

More texts on Egger-Lienz

Albin Egger-Lienz – The Nameless

World War I was not only fought with guns, cannons and bombs but also with an unprecedented flood of images … Within this “trench impressionism”, one artist stands out like an erratic rock with his paintings: Albin Egger-Lienz …

Fundamental Life Story

He needs for his work … the entire circle of life: “Love (procreation), the mother, the children, the struggle, the regret and awareness … It is the mind of a painter who, inspired by the symbolist zeitgeist, wants to provide a setting for fundamental questions of existence through powerful images …