Fundamental Life Story

Egger-Lienz’s Image of the Mother in the Context of his Contemporaries

Carl Kraus (Appeared in: Egger-Lienz and Otto Dix. Bilderwelten zwischen den Kriegen, exhibition catalog published by Wolfgang Meighörner, Red. Helena Perena, Astrid Flögel, Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck 2019)

He needs for his work, in order to fully invest himself, the entire circle of life, writes Egger-Lienz in June 1912 to his friend Otto Kunz: “Love (procreation), the mother, the children, the struggle, the regret and awareness. The silence of action, and the creator himself. I mean basic[c]hords (fundamental life story), which grip my soul and through which my creative impulses can be satisfied.”

It is the mind of a painter who, inspired by the symbolist zeitgeist, wants to provide a setting for fundamental questions of existence through powerful images, with the conviction that everyone’s fate is subject to universally valid rules. This is true for man and “woman”, who are assigned clearly defined tasks in life. That for human existence and nature collectively, a central theme of the mother is recurring throughout the work of the artist: from the early “Heiligen Nacht” (Holy Night) to the works “Das Leben” (Life) and “Zeugung” (Procreation) in the middle phase to “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women) and the later thought images “Mütter” (Mothers) and “Pietà”.

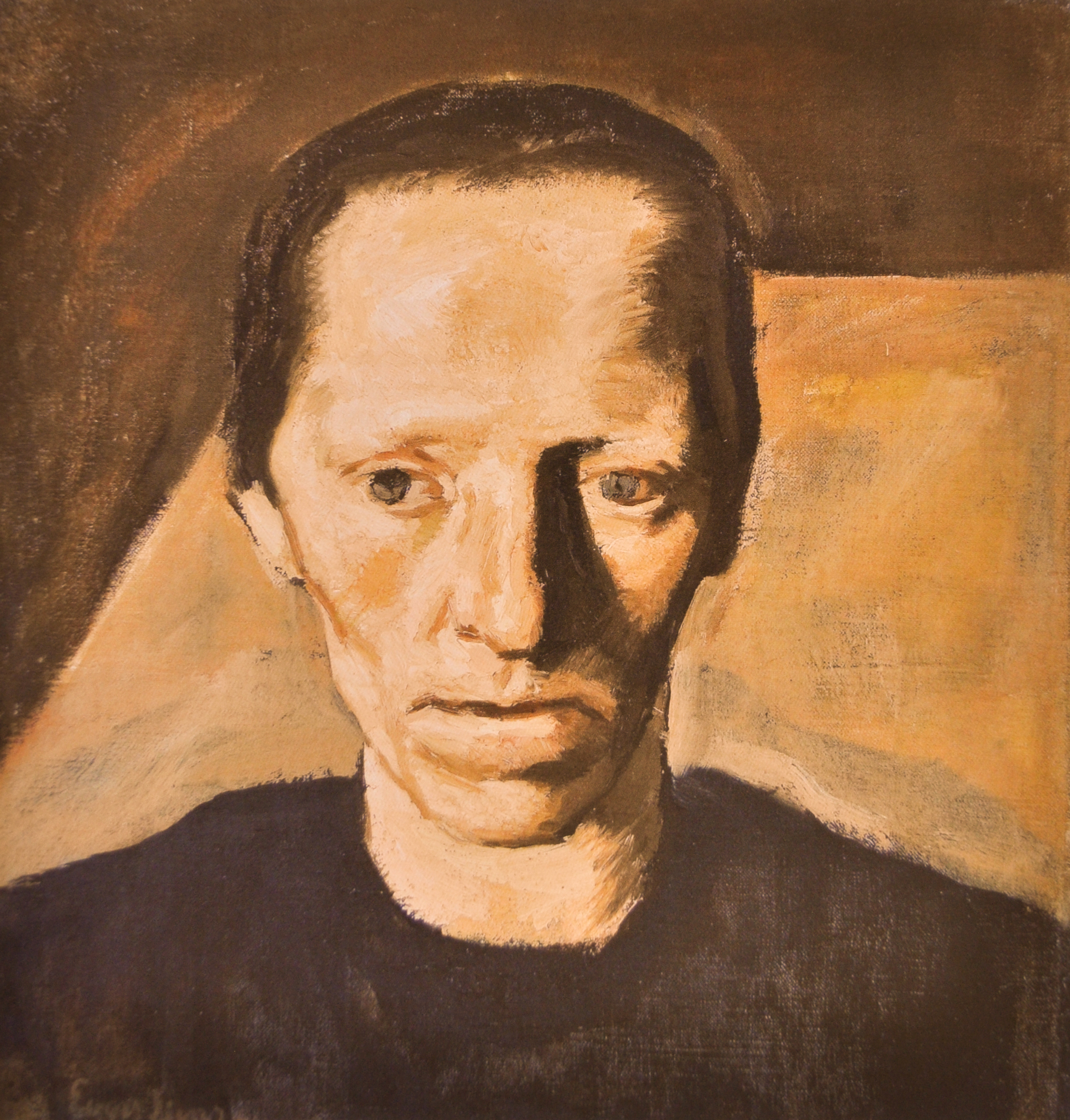

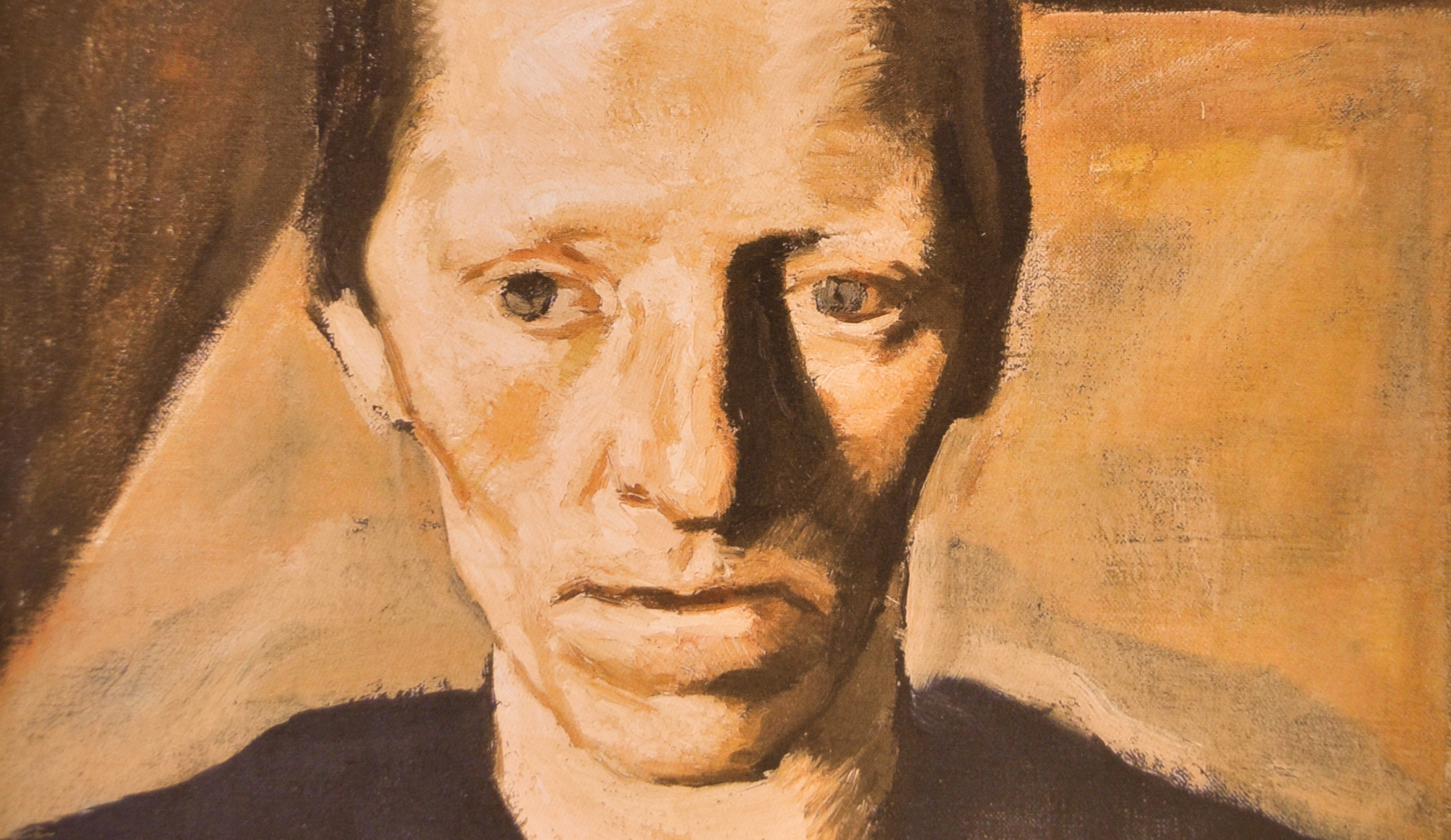

Head study of the woman on the left in “Mütter” (Mothers), 1922 (Kirschl M 564; Bozner Kunstauktionen).

The “Pietà” is the last theme that Egger-Lienz occupies himself with and the consequent realization of his artistic desires, one final concentration of form and content. Everything is reduced to the essentials and through the renunciation of forced stylization exhibits great expressiveness. Iconographically, the image corresponds more to the tradition of “lamentation”, as it is three women holding a wake for the dead body of Christ lying on a table. Their grief is, however, cautious and has given way to the certainty that the death of the Man from Nazareth gives their lives ultimate meaning. It is left open as to whether one of the women is his mother, the three of them are much more representative of all mothers and womenIt is evident that the mother, the great wondrous creator, has offered a fundamental theme to artistic expression in painting and sculpture from the beginning, thereby acting as an immediate mirror to social change. This theme is also picked up by countless contemporaries of Egger-Lienz, between Realism, Symbolism, Expressionism and New Objectivity, from Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) and Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) to Max Beckmann (1884-1950, Otto Dix and Rudolf Wacker (1893-1939). Egger-Lienz’s specific interpretation, in part conservative and shaped by old farmers’ traditions, which the National Socialist cultural policy – picking out certain aspects – later appropriates for its purposes, becomes especially clear in comparison to these artists. What also becomes apparent is how the impressive development of the painter leads to timeless statements far from any “blood and earth” ideology (See also: Zwischen Ideologie, Anpassung und Verfolgung. Art and National Socialism in Tyrol, Catalog Tyrolean State Museum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck 2018/2019).

„To me, my mother was love itself“

As Egger-Lienz, at the start of 1898, tells of his past through multiple letters to his fiancée Laura von Möllwald (1877-1967), he begins his story with a crucial scene that seems to have been imprinted in the artist’s memory: With tears in her eyes, his (foster) mother can no longer look on at how apathetically the farmer couple with which he spent his first year of life cares for him during a severe case of a “throat disease” and consequently takes him in immediately with herself and his father (1835-1907). That Franziska Rotschopf (1840-1896), who his father married a few months after Egger-Lienz’s birth, is not his birth mother, was only revealed to him when he was already at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich: “To me, my mother was love itself, yes it often seemed to me that I was favored by her. For my outstanding mother wanted to wreck the reputation of the stepmother. As I came home from the academy for the third time to spend my vacation there, my father said on a walk the following words to me. You are now old enough that you can be entrusted with more serious matters. The woman that you always have taken for your mother is not your birth mother. Your mother, who is a fine woman, lives, I think, happily married abroad. Fate did not want us to be bound together forever […] We have kept this truth secret so that you should never feel that your real mother is not with you. Isn’t it true that you have never felt this and that you have had a rightful and loving mother up to now? With tears in my eyes, I had to confirm this wholeheartedly, as a mother had never cared for a child so maternally and warmly.”

Egger-Lienz’s relationship to his foster mother, who treats him in exactly the same way as she does her own three children, remains close up to Rotschopf’s death. He only meets his birth mother, the farmer’s daughter from Lienz Maria Trojer (1845-1914), for the first time in 1895 as a seriously ill patient at a hospital in Milan. He develops a loving relationship with her as well.

Egger-Lienz painted several portraits of both his foster mother and his birth mother, the latter, among others, in a powerful drawing from the year 1912 that can be contrasted with the work “Unsere Mutter” (Our Mother) of his best student in Weimar, Rudolf Wacker. Both depict common farm women, scarred by their lives, whereby the image made by Wacker, who belongs to a younger generation and is characterized by Expressionism and New Objectivity, reveals more bluntly executed features.

In his letters to his fiancée, Egger-Lienz clearly expresses his image of women, which was a typical one for the time. How covetable the woman is, when she has a sense of domesticity, loves her spouse and grants her kids an attentive upbringing: “It always seems to me that a woman without a man can never fulfill her mission in life, just as a man without a woman can never be anything and above all is only half a man. How bleakly his existence goes on, never really attaining happiness from achievements he worked for since nobody stands by him who can share his happiness.” The painter expresses this even more clearly in his third year of marriage: “You know, I don’t need a so-called witty, educated woman; a bluestocking is something awful or even a painter, she would understand everything better and would want to meddle in all sorts of things”. Had the students who Egger-Lienz taught in his 1903-1904 “Painting school for women” in Vienna read this declaration, they would have undoubtedly been amused.

Good mother, evil mother

During this first time in Vienna, Egger-Lienz picks up on a theme that he had already been inspired by one and a half decades ago. At an exhibition in Munich in 1888, he saw Fritz von Uhde’s (1848-1911) triptych “Heilige Nacht” (Holy Night) for the first time and was deeply impressed by its realistic yet intimate characterizations. However, not until 1903 would he paint his own “Heilige Nacht” (Holy Night). As is typical to his creative process, the painter first produced many sketches and studies for the final painting, particularly in the Cadore and Dolomite regions. Uhde’s composition, which served as his conceptual groundwork, was transformed through his own ideas of imagery and reimagined the triptych form, among others, as having spatial unity. In it, it is night and Maria and the baby Jesus are in the stable, dipped in the warm, magical light of a lantern that also gently illuminates Joseph, a handmaid and the shepherds – an image that emerged from deep emotions, as the artist’s son Fred (1903-1974), born in January 1903, served as his model for the baby Jesus.

With “Heiligen Nacht” (Holy Night), Egger-Lienz effectively established an ideal image of the mother with child, which was often repeated in later years. This stands in glaring opposition to a work that his (Italian-)Tyrolean compatriot Giovanni Segantini had painted a decade earlier: “Die bösen Mütter” (The Evil Mothers). Here, in a cold winter landscape, a half-naked pregnant redheaded woman with an infant at her breast is tangled up in a tree. It is the artistic condemnation of mothers who don’t look after their children. The work emerged from the artist’s childhood trauma: Segantini was not as lucky as Egger-Lienz was as a child, as he lost his mother (and a brother) early in life and was abandoned by his sister.

Man and Wife

The precisely defined place of man and woman within Egger-Lienz’s worldview is deeply rooted in his Catholic origins and in his work, the use of the term “Weib (Wife)” has a traditional, biblical character, in contrast to Otto Dix’s use of the word. When Dix speaks of “Weibern (women)” as preferential to the more direct – “Weib (woman)” denotes, to him, the sexually independent woman in general, more specifically the prostitute. Thereby, to him, the “sinners” – the whore and her client – are still “the first to get into heaven”.

In Egger-Lienz’s “Wallfahrern” (The Pilgrims), which he painted at the start of his middle monumental-decorative phase, women and men are strictly separated from one another. Through a triptych-like divided beam construction, we see the women on the left side, the men on the right, such that a woman and a man flank the crucified Christ in the center.

In the major works that followed, Egger-Lienz repeatedly makes man and woman the focus, such as in, at the end of the Vienna period, the monumental image “Das Leben” (Life) (also “Die Lebensalter” [The Ages of Life]) which was the result of various initial designs: “5 male figures and a pregnant woman. Life-size, all at the construction of a log house […] Boys to old men (90 year-old man), that step into the pit.” This image idea is not new: it was realized, for example, by Akseli Gallèn-Kallela (1865-1931), a Finnish painter who was already very well-known in 1900 Austria. In his painting “Nybygge/Hausbau” (Building) (1903), two men erect a log house while a breastfeeding mother is shown in the foreground. However, nobody had executed this motif as effectively as this Tyroler painter had.

This monumental, symbolically-charged character inspired extensive interpretations by contemporary art critics as well as writers, among them the “Jungtiroler” playwright Franz Kranewitter (1860-1938) who, according to his exuberant review, recognizes “the eternal becoming, blossoming, fruit-bearing and dying glorifying song and mysterious allegory” in the work, “fathered and born from the same spirit, from which Michel Angelo’s ‘Night’ and the other colossal figures rise at the tomb of Pope Julius II.” The woman that in “endless simplicity and modesty, in bitter grace” stands next to the man, knows what is destined for her “a moving devotion, a gentle, motherly endurance, like the English greeting so lovely expressed with the words of the Mother of God: ‘See, I am a handmaid of the Lord’, lies above their faces, that despite its unattractiveness, indeed the ugliness of individual parts, with his endless, no longer vulnerable grace and tolerance almost carries a shimmer of the heavens and reaches deep into our hearts. Strong desire there and sorrowful, calm sufference here, activity and passivity, both poles of the magnet, dissonance and harmony, I’ve never seen it so largely, simply, vividly and eloquently represented as it is here.” The painter and critic Max von Esterle (1870-1947) remains prosaic and reserved in his “Art Review” published in the “Brenner”: He points out above all the differences between the Tyrolean painter and his Swiss antipode Ferdinand Hodler who has a richer and differentiated nature, a broader ability, more diverse set of mediums and a more complex symbolism, “but Egger, the modest, born with the will for simplicity”, is through his sculptural perception, in his grandiose one sidedness and in his simple mysticism, far more monumental. With this in mind, Egger-Lienz is undoubtedly also more monumental than Gustav Klimt, who at times selected comparable symbolistic themes for his large compositions (“Die drei Lebensalter” (The Three Ages) [1905]; “Tod und Leben” (Death and Life)[1911-1915] etc.) and in doing so demonstrates a highly aesthetically decorative and erotically psychological refinement that is even more foreign to Egger-Lienz than Hodler’s more “down-to-earth” conception.

“Das Leben” (Life) is also recognized by Esterle as the highlight of Egger-Lienz’s work thus far, everything produced beforehand being merely a “prelude”. From today’s perspective this assessment obviously seems excessive, the painting is more closely an example of one of temporary convention and cautious approach in contrast to his later, entirely unconventional works, in which his purely painterly qualities rightfully return.

Procreation and Birth

Egger-Lienz’s “Entwurf zu ‘Zeugung’” (Study for Procreation) (1913/1914), created as one part of his “fundamental life story” series inspired by the four seasons, and one of the Tyrolean artist’s most curious concepts, stands in stark contrast to Klimt’s compositions. A woman lies on a bed, motionless and deathly pale, her body represented as severely shortened as is the dead Christ figure in the later work “Pietà”. While a colossally sized old man leans forward from behind the figure, symbolizing the end of the circle of life, a man storms in from the right side with outstretched arms ready “for procreation”. The whole scene seems as if out of a nightmare, man and woman merely fulfilling their duty far removed from any eros, subjugated by fate, where the end is ever present.

Firstly, the allegorization of spring as represented in the series was originally planned by Egger-Lienz as the image of a woman giving birth between two crouching women, one of which breastfeeds an infant, an undoubtedly bold motif that he later inserts in more abstracted form into “Der Mensch” (The Human). However, the artist never develops “Werden” (Becoming) (also “Geburt” [Birth]) just as he never completes “Zeugung” (Procreation) and later even destroys the sketches for it. Through photo documentation from his estate, one can gauge how consistently Egger-Lienz realized his visual concepts. With all compositional balance thanks to a classical triangular structure it is a work of exceptionally powerful expression and directness. Having said this, the drastic realism of Otto Dix’s “Geburt” (Birth) (1927) perhaps is missing. There, the birthing mother is represented close up as just a lower torso with splayed legs, the pubic area barely cloaked by a sheet, while the blue umbilical cord still hangs from the newborn.

War Women

Women had their place in Egger-Lienz’s World War I works as well. After his trilogy “Den Namenlosen 1914” (The Nameless 1914), “Missa Eroica” and “Finale”, dedicated to the soldiers on the front, he brings another often dismissed aspect of war into the discussion with “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women) (1918-1922). In disillusioned realization that war for them was a burden that they had no say in, in mourning their husbands and sons killed on the battlefields, these women’s faces are hardened into wooden masks, contorted with pain. To this radical declaration the painter links an equally radical design. Hardening of form and rigorous subordination of all parts of the image within a severe geometric composition – two significant principles of “spatial composition” in Egger-Lienz’s final creative period – connects his work here more than ever with a completely expression-serving deformation and cubified fragmentation of form, thereby demonstrating, like in the previous war images and later thought images, avant-garde characteristics of an international level.

It is also interesting to compare “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women) with Max Beckmann’s

“Frauenbad” (Women‘s Bath), which was also created immediately following the end of the world war. It shows the German painter at the high point of his expressive phase as well, with closely compacted figures on a tightly cubistically fragmented spatial field. One can see a bizarre jumble of women of various ages in bathing costumes with children playing and crawling in between as well as a mother with a squirming boy who squeals in her strong embrace and flashes an ugly grimace. He has a paper helmet on his head, folded up from the newspaper “Vorwärts”. The racy slogan means to say that the boy, despite the disasters in the streets, after the horrors of war, still feels attracted to power, weapons and strong men. A similarly direct, socially critical emphasis is missing from “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women). However, even this representation, in contrast to earlier images of mothers by Egger-Lienz and acquired in 1941 through the “Reichsgau Kärnten”, was difficult to exploit by the National Socialists with their “Aryan race” and their new generation of soldiers served by the mother cult.

Mothers, Pietà

Although the “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women) mark an end and a turning point in the painter’s artistic development, the theme of the woman, or rather the mother, is still present in

Egger-Lienz’s later thought images in which extreme expressive deformation gives way to previously unreachable contemplative introspection. This comes up repeatedly: from

“Generationen” (Generations), in which a mother with child is naturally included, to “Mütter”

(Mothers) (1922/1923) to the magnificent end point that is “Pietà”. Egger-Lienz’s artistic conviction in the subordination of the creative means under a “big substance” – which is as much reason for him being considered an outsider within contemporary art as are his rural subject matters – comes to completion in his last “images in a state of contemplation ”.

Thematically and compositionally following “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women), “Mütter” (Mothers) again shows three women that, in the absence of their husbands who had perished in battle, are on their own: one takes up the painting’s foreground, another looks through a window into the room and a somewhat younger one set slightly back holds a swaddled baby in her lap with both hands. Unlike in “Kriegsfrauen” (War Women), the painter also uses an additional image element. An oversized crucified Christ, seemingly resting on the tabletop, stands diagonally in the room. He is the one who provides support in times of distress: the early Egger-Lienz biographer Josef Soyka notes “as already present in ‘Kriegsfrauen’ (War Women), their eyes, their detached, lost gazes”, “such are the expressions of the ‘Mütter’ (Mothers), heightened toward the visionary: these mothers are no longer plagued by earthly troubles, they had already recognized them as being useless a long time ago.”

The “Pietà” is the last theme that Egger-Lienz occupies himself with and the consequent realization of his artistic desires, one final concentration of form and content. Everything is reduced to the essentials and through the renunciation of forced stylization exhibits great expressiveness. Iconographically, the image corresponds more to the tradition of “lamentation”, as it is three women holding a wake for the dead body of Christ lying on a table. Their grief is, however, cautious and has given way to the certainty that the death of the Man from Nazareth gives their lives ultimate meaning. It is left open as to whether one of the women is his mother, the three of them are much more representative of all mothers and women.

“The richness of substance in “Pietà”, Rudolf Leopold states in an interview, “could be most closely likened to early works of [Pablo] Picasso [1881-1973]. Even though this artist […] in his ‘Rose Period’ was chronologically earlier, Egger-Lienz reached an even greater richness of substance in this painting. “Pietà” hung directly over the collector’s bed. 14 years after he removed it and included it in the Leopold foundation, “the mounting strings and hooks still hang there empty. I haven’t found another painting yet that could replace this one.”

As the painter Leopold Hauer (1896-1984) visited with Egger-Lienz at Grünwaldhof in St. Justina shortly before his death and asked him what he’s working on now, he is given the reply: “I am finished.” These words are spoken not only out of the ill man’s resignation and exhaustion, but also out of the awareness that he had said all he had to say. Particularly in respect to the image of the mother.

Cited letters of Egger-Lienz from: Kirschl, Wilfried: Albin Egger-Lienz. Das Gesamtwerk, Wien-München 1996; Egger-Lienz, Ila: Mein Vater Albin Egger-Lienz, Thaur o. J. [1981]

More texts on Egger-Lienz

Albin Egger-Lienz (1868–1926)

Many labels have been attached to Albin Egger-Lienz: late historical painter, peasant painter, regional artist, blood and earth painter … What cannot be overlooked, however, is the fact that Egger, above all else, was continually searching for new forms of expression …

Albin Egger-Lienz – The Nameless

World War I was not only fought with guns, cannons and bombs but also with an unprecedented flood of images … Within this “trench impressionism”, one artist stands out like an erratic rock with his paintings: Albin Egger-Lienz …